Here at ArtsHacker, we’ve been warning arts admins against the practice of using sliders and carousels as a strategy to deliver mutually exclusive messages within a single space as far back as 2016. But just like a stubborn viral bug, the idea that carousels somehow function as a magical message delivery platform that delivers high conversion rates is difficult to shake.

Fortunately, there’s a great article by front-end and User Experience (UX) professional Vitaly Friedman in the 4/13/2022 edition of SmashingMagazine.com that takes a super deep dive into the subject.

Right out of the gate, Friedman reminds readers about the bad reputation carousels have among UX experts. He provides a wealth of recent research resources that quantify just how poorly carousels perform.

Most arts and culture organizations attempt to use carousels for content discovery, which Friedman points out is exactly where they have counterproductive results.

“Carousels are also a poor choice when it comes to content discovery. If something important is presented in one of the later slides of a carousel, a vast majority of users will experience severe issues discovering it. Not surprising: if something is important, we should probably not hide it.”

One of the most common examples of content discovery use at arts and culture org websites is stuffing as carousel with several upcoming shows or mixing that with mutually exclusive slides for fundraising and education messages.

The Narrow Instances Where Carousels Work

It’s worth pointing out that carousels aren’t all bad. In fact, there are very specific instances where they can produce excellent engagement results and promote conversion.

Friedman sums this up by saying they work best when there’s a need to highlight multiple features or options but lack the space to display them at once in ways that conform to UX best practices.

“Carousels can be quite effective…[and] there are a few contexts in which carousels perform fairly well though. This holds true especially if a carousel is meaningfully integrated into a task that a user is trying to complete… In other words, carousels work when we provide additional content within a specific, and relevant context.“

He goes on to provide a concise list of specific examples, here are a few of the key items from that list which are especially applicable to arts and culture org uses:

- users are exploring an appropriate option, or choose a pricing plan,

- users want to preview an experience they want to book (hotel, vacation, museum, theatre, restaurants) — in cases when they want to see large fullscreen images or videoswhile still being able to navigate between them back and forth,

Let’s apply each of those to a few common arts org scenarios.

- Pricing plans: traditional event subscriptions, ticket packages, memberships, and benefit driven donations. For subscriptions and ticket packages, a carousel can be useful for displaying information about each event, especially if it’s a choose your own or flex pack scenario where there could be as many as a dozen or more events for ticket buyers to consider. For memberships, providing a card detailing benefitsor even breaking down longer lists of benefits for a single membership option can be useful.

- Preview an experience: When applied to something like a reserved or general admission seating ticket purchase path, a carousel that includes images such as the view from the seat/section along with other key venue images (lobby, bathrooms, concession stands, ticket office, etc.) can be very effective. For groups that provide a large number of images for the event, like theatres, dance, and museums, a carousel can deliver all those images in a compact space.

When In Doubt

Friedman offers some frank advice toward the end of his article. He also provides a good dose of empathy for those who keep getting requests from decision maker levels about including carousels and how you can effectively push back (emphasis added).

I’m yet to see a carousel that slashes all expectations by large and drives KPIs through the roof…I always have to argue about design decisions based on evidence coming from usability and accessibility tests, and rely on business metrics to drive these decisions.

Carousels rarely help in driving these metrics — mostly because they hide relevant content and hence make it less accessible…If you have a strong feeling that a carousel isn’t really working, or is just the wrong component to use, run a test on a Saturday morning when there might be less traffic, and build up a case highlighting that another design might be driving higher KPIs.

Your homepage is likely one of the hottest battlegrounds for internal discussions and what I typically suggest to clients is exactly what Friedman purports for alternatives to carousels that perform much better.

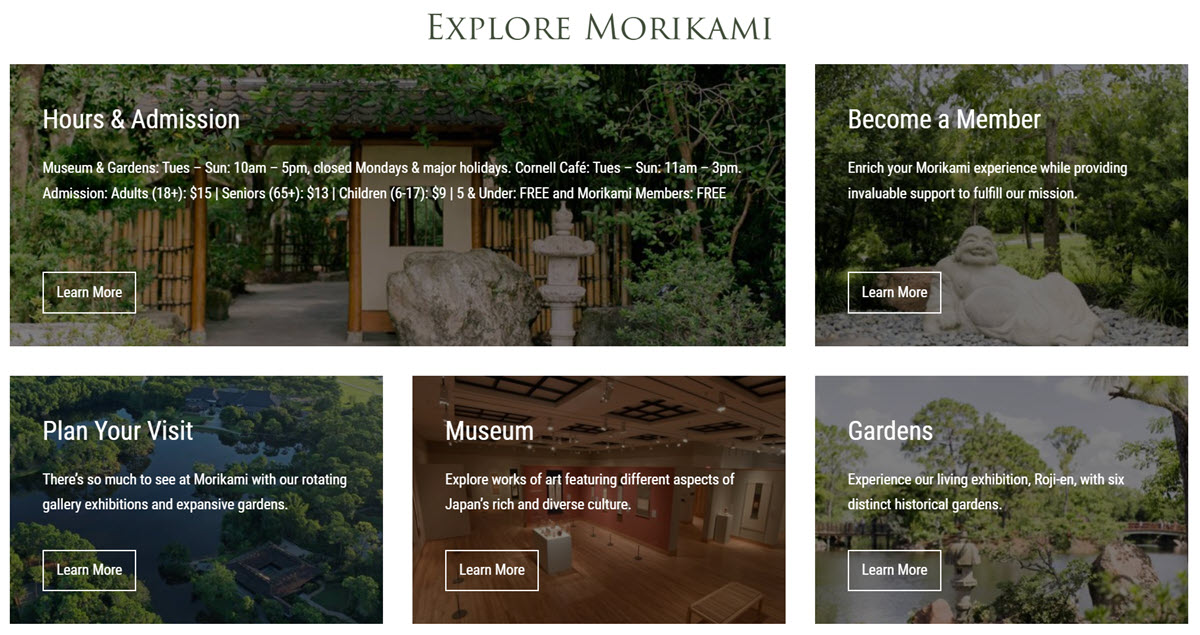

One of the most effective options that is straightforward to design and maintain is a masonry card layout with tight copy and rigorous art design. Here’s an example from morikami.org:

In the end, if there’s every any question about whether you should use a carousel or slider, you should avoid it.