There’s this sinking feeling you get when you delete a file or revise something you’ve been writing and forget to save.

It’s like, “Wait, what did I just click OK about?”

The system asks you if you are sure and you get so used to clicking OK, that you just do. That’s when you realize you just agreed that your hard work can be safely deleted forever.

Maybe you immediately open Google and try find someone that knows how to recover lost work. Sometimes you get lucky and find a link like this ArtsHacker post about recovering deleted MS Word files.

As I programmer, while I know the feeling, it is rare for me.

Programmers have tools to help with exactly this problem; they are so good at what they do it means far less stress when working on large and/or projects drawn out over long periods of time.

Even though these were originally designed as tools for programmers, they’ve evolved to a point where they are just as useful for a broad application of projects.

It might be worth looking at what they do and see if it might be applicable or useful to you.

The Best Of These Tools Is Version Control

This where you have content (a document, a composition, or a code) in a system that automatically tracks when changes happen and exactly what changes were made.

You can go back and explore checkpoints, often with descriptions of what was changed, and if necessary revert back to those earlier versions.

You might have a certain amount of this around yourself and not realize it. Microsoft Word, for example, does automatically save and has built-in tools (if you turn them on) for revision history.

If you keep your files on DropBox, there is at least a limited ability to recover deleted files or see previous versions. But it doesn’t take much time for that method to become cluttered and confusing; it’s closer to digital hording than serving as an effective version control tool.

Gitty Up

I use a tool called Git, with hosting on BitBucket by Atlassian. I’ve also used GitHub, which is free, but primarily for open source software.

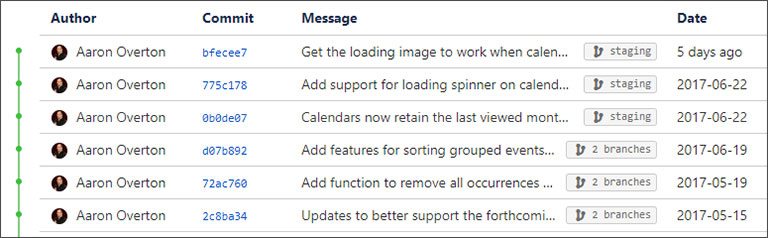

You can begin to get a good idea of just how organized and streamlined a creation process becomes when you look at some history of changes I made to a piece of software I was working on:

Every time I make a change, I “commit” those changes to a “repository” of code. I add a comment about what I did.

Since I’m innately lazy and it’s tempting to just commit without a comment, I turn on a feature that requires me to write something before submitting the commit. If you’re like me, you’re far more likely to write something meaningful if it’s a requirement. #knowtheyself

The blue number sequences in the “Commit” column are unique identification numbers to that specific change. Selecting one will show exactly what files were changed, what lines were added, deleted, or modified, and give me access to undoing those changes.

Even though this example is all about writing code, that doesn’t mean you’re restricted to using this tool for geek stuff.

For example, let’s look at this from a composer’s or playwright’s perspective.

Composers often use Finale or Sibeleous to write their music while writers may use Final Draft or Celtx.

Regardless the medium, these programs simply save files so from that perspective, it’s just content.

Version control software doesn’t care what the content* is, it just wants to make you happy by tracking the changes.

If you put your composition, play, or program notes content into a version control system, you create a living memory of those changes.

For example, let’s say a composer removes a second oboe part. S/he can commit that change, save the related copy (i.e. content), and it’s no big deal.

The prior version isn’t gone, it’s just tracked as an incremental difference while the version you work on locally (i.e. your desktop or laptop) is where you spend your focus moving forward.

Version control gives you the ability to get that part back anywhere down the road.

This becomes super useful if you need to circle back to create a version for reduced orchestra several months, or even years, down the road. Or perhaps after hearing the first rehearsal, you really want that second oboe part back.

For added sophistication, you can “tag” a release**, just like software and apps do; i.e. v1.2.5.

This provides a snapshot of what you did at a given point of time for easy access. You can also “branch” your files, which makes a copy of where you are at a given point from which you can experiment freely and safely. When you’re done experimenting, you can abandon that branch if you don’t like where it went or “merge” your changes back into the main branch if you want to keep them.

It doesn’t take much to see where this becomes useful when creating arrangements or variations of your work based on where and who is involved in the performance.

This is just one example showing how programmers use best practices to shape their workflow toward improved productivity. It also lets us work without being particularly worried about losing anything.

Of course, you can continue using the digital hoarder method and save multiple versions with different filenames.

But aren’t you tired of wondering which version of blah_old.doc to use?

Was it blah_old_v1.docx…or…blah_old_final.docx?

Wait, maybe it was blah_old_NO_use_THIS_one.docx…or…blah_old_NO_REALLY_use_this_one.docx.

[box]

* One caveat: large binary files are not really stored efficiently in this type of tool, so if you are doing photo or video editing, there are better tools out there. Nonetheless, the basic principles of version control still apply.

**Adding release numbers to parts is another clever way to help prevent piracy. For example, if your work is only available as a rental and you find a group using parts with a version that is no longer in circulation, you will have an easier time tracking down where the theft occurred.

[/box]