I have written before about how to discover the True Cost of organizational programs. This is helpful when it comes to budgeting, evaluating your programs and soliciting support for those programs.

In April 2016, Non-Profit Quarterly hosted a webinar that addressed this last activity–making the case to funders cover the Full Cost of programs. The webinar was conducted by Claire Knowlton, Director in Advisory Services at the Nonprofit Finance Fund.

Even if you don’t intend to press funders for more comprehensive support, the webinar is helpful in understanding the different categories that comprise an organization’s costs.

There is a lot of discussion these days about funding non-profit overhead and not using overhead ratio as a measure of organization effectiveness. Knowlton says that overhead is too narrow a focus and that the conversation should really be about fully funding program expenses.

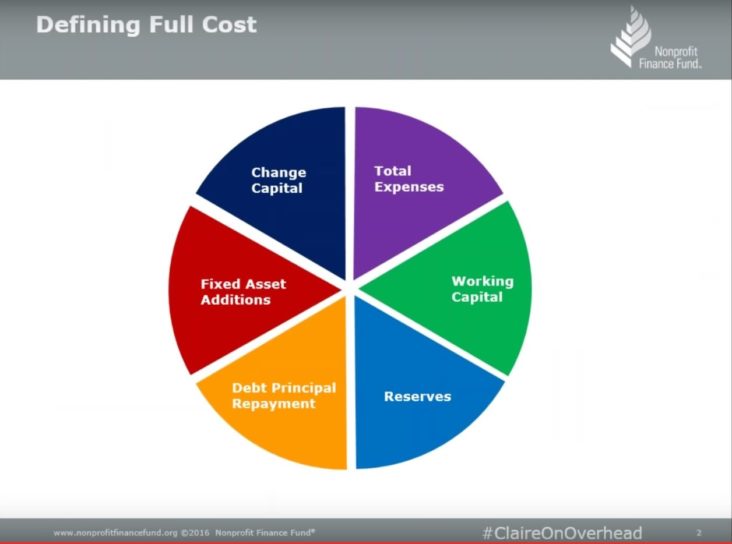

Before you can have a conversation about full costs, there needs to be a more refined understanding of what they are. Typically an organization defines their full costs as Program Expenses plus Overhead Expenses, but Knowlton says is can be broken down much further.

She cautions that you not interpret the fact the wedges are of equal size to mean they will carry equal weight and importance in every organization.

As she defines each of these categories, she discussed how accessible the money should be to management. For example, sometimes reserves may need board approval to use.

She clarifies what each categories does and does not include. For example,

Unfunded expense – expenses that are not currently incurred that if covered would allow the organization to work at their current level in a way that is reasonable and fair – sweat equity (overworking and underpaying staff), sub par supplies, slow internet.

-Expense to expand or do more are not counted in this.

Reserves – protect against risk by covering short term deficit- allow for trial error, take artistic risk, experiment with new approaches

-you get reserves by budgeting to allow for a little surplus year over year. Knowlton comments that foundations and boards need to let go of the idea of zero bottom line budgets.

The category she spent the most focus on was Change Capital.

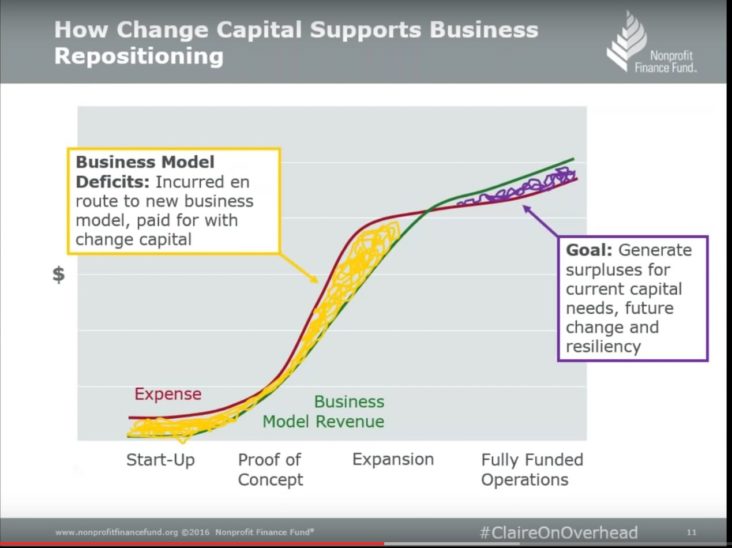

Change Capital –Periodic reinvestment into the organization to change its business model. (the size or reach of mission and/or how it makes and spends money)

-Covers upfront costs of change and deficits until business model revenue exceeds new business model expenses. It might cover costs of new development person as things expand.

-Should include funds for the launch/scale of revenue generating activities that will sustain organization when change capital is spent

-Typically large, flexible, multi-year funding from an external source. NOT self-funded, organic growth

Knowlton suggests that rural arts organizations in particular might employ change capital to shift their business models because they so often have difficulty identifying entities who are interested in funding their geographic region.

Knowlton says that an effective Change Capital partner is going to be one which is more about relationships than “deliver me X outcome for $50,000.” There has to be a lot of conversation about goals, true costs, etc. This is especially true when it comes to reporting revenue and expenses on an annual basis because funders aren’t used to seeing change capital being accounted for in financial reports.

The following graphic illustrates the arc of revenue and expenses of a change from start up, proof of concept, expansion to fully funded and places where change capital is replaced with ordinary revenue.

Toward the end of the webinar (around 42:30) Knowlton addresses the idea of trying to reduce expenses by eliminating programs by cautioning organizations to look carefully at the direct costs of shuttering the program. She says we are used to looking at costs in terms of what is allocated to them. Once you look closer, may discover the expenses which actually go away if you shutter it aren’t as large as you may imagine. You may discover shuttering the program makes it worse. Funding it was bringing in might have been offsetting some of the indirect expenses.

Using some of the tools and processes I mention in my post about True Cost of Programs may assist in this evaluation.